The cost to transport containerized goods peaked at unprecedented levels in late 2021. That cost has been falling ever since. In contrast, the cost to rent ships that carry containerized goods held up much longer. Even as freight indexes slid month after month, charter indexes stayed near record highs into this summer.

No longer. Indexes that measure container-ship rental rates are now dropping like a stone, suffering far steeper declines than freight indexes. Ship-charter indexes have nose-dived in recent weeks.

“What is astonishing is how quickly the market appears to turn,” said ship brokerage Braemar on Monday. “only some weeks ago, charter rates appeared stable and operators were still securing forward tonnage at historically high rates on long-term periods.”

The fact that liner companies are suddenly less interested in renting container ships — and when they are, they pay less and lease for shorter periods — can only mean one thing: Liner sentiment toward the freight market’s future supply-demand balance has deteriorated.

Charter indexes falling fast

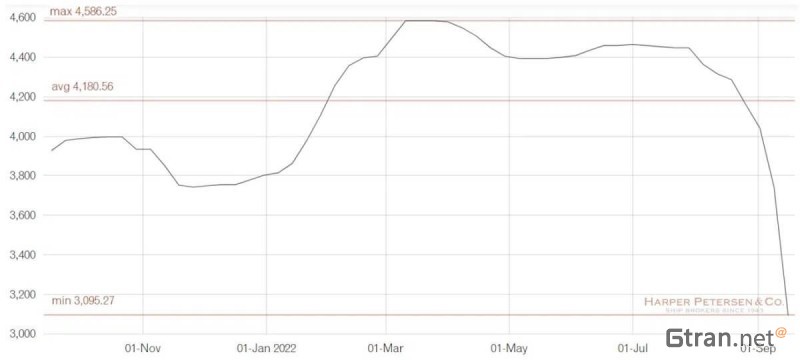

The Harpex index, published by brokerage Harper Petersen & Co. since 2004, hit an all-time high of 4,586 points in late March. It stayed in the vicinity of that peak, in the low 4,400s, until late July. As of Friday, it had collapsed all the way down to 3,095 points, sinking 30% in just eight weeks and 18% versus the previous week. The Harpex is now down back to July 2021 levels, albeit still four to five times higher than pre-COVID.

Harpex index (Chart: Harper Petersen & Co.)

Braemar’s BOXi index was at 317 points on Monday, plunging 30% in the past week alone. The BOXi index was at 580 points in late July. It fell 45% in just six weeks.

The charter index of brokerage Clarksons plunged 26% last week, although it’s still four times pre-COVID levels.

According to Clarksons Securities analyst Frode Mørkedal, “Softening has been most obvious in the feeder sector in recent weeks. But the consequence of dropping freight rates is now further eroding [charter] hire rates in the bigger size ranges, even while tonnage availability remains constrained.”

Braemar likewise cited weakness among the smallest ships. “In the feeder market below 2,000 TEUs [twenty-foot equivalent units], we are seeing the biggest build-up of open tonnage and it is across all regions.”

Braemar also sees trouble brewing for midsize ships. It highlighted a recent six-month charter of a smaller Panamax-class vessel at $50,000 per day for a period of only six months. “It is about three months ago when similar-sized vessels were still able to get five-year employment at similar rate levels,” Braemar said.

Wave of newbuildings in 2023-24

When container lines leased ships for four to five years at historically high charter rates during the 2021-22 peak, it didn’t mean that liner execs believed freight rates would stay high for the next four to five years.

Rather, it meant that liners believed they’d make so much from high freight rates at the front end of charters that they’d come out on top even if they gave back some of those profits in the later years by continuing to pay high rents when freight income was much lower.

Freight rates were so high at the market apex in late 2021 that even after they initially started to descend, they continued to provide exceptionally high income in relation to liners’ ship-chartering costs. Ocean carriers continued to rack up record quarters in the first half of 2022. Carriers remained confident enough in freight earnings to continue leasing container ships at very high rates. As a result, steadily high charter indexes diverged from falling freight indexes.

The swiftness and severity of the recent charter-market index decline — closing the gap with freight-index trends — implies a change in liner confidence toward freight earnings.

The container-ship orderbook looms ever larger. According to Clarksons Securities, tonnage on order is now 27.3% of tonnage on the water. Of new deliveries, 75% of tonnage will be delivered in 2023-24.

In past cycles, when liners had too many newbuild deliveries for freight demand to fill, they let ship leases expire. If they signed renewals or leased new ships, they paid much lower charter rates. They laid up excess vessels and reduced sailing speeds.

At the bottom of the last cycle, when Hanjin went bankrupt in 2016, the Harpex hit a nadir of 314 points, one-tenth of the index’s current level.